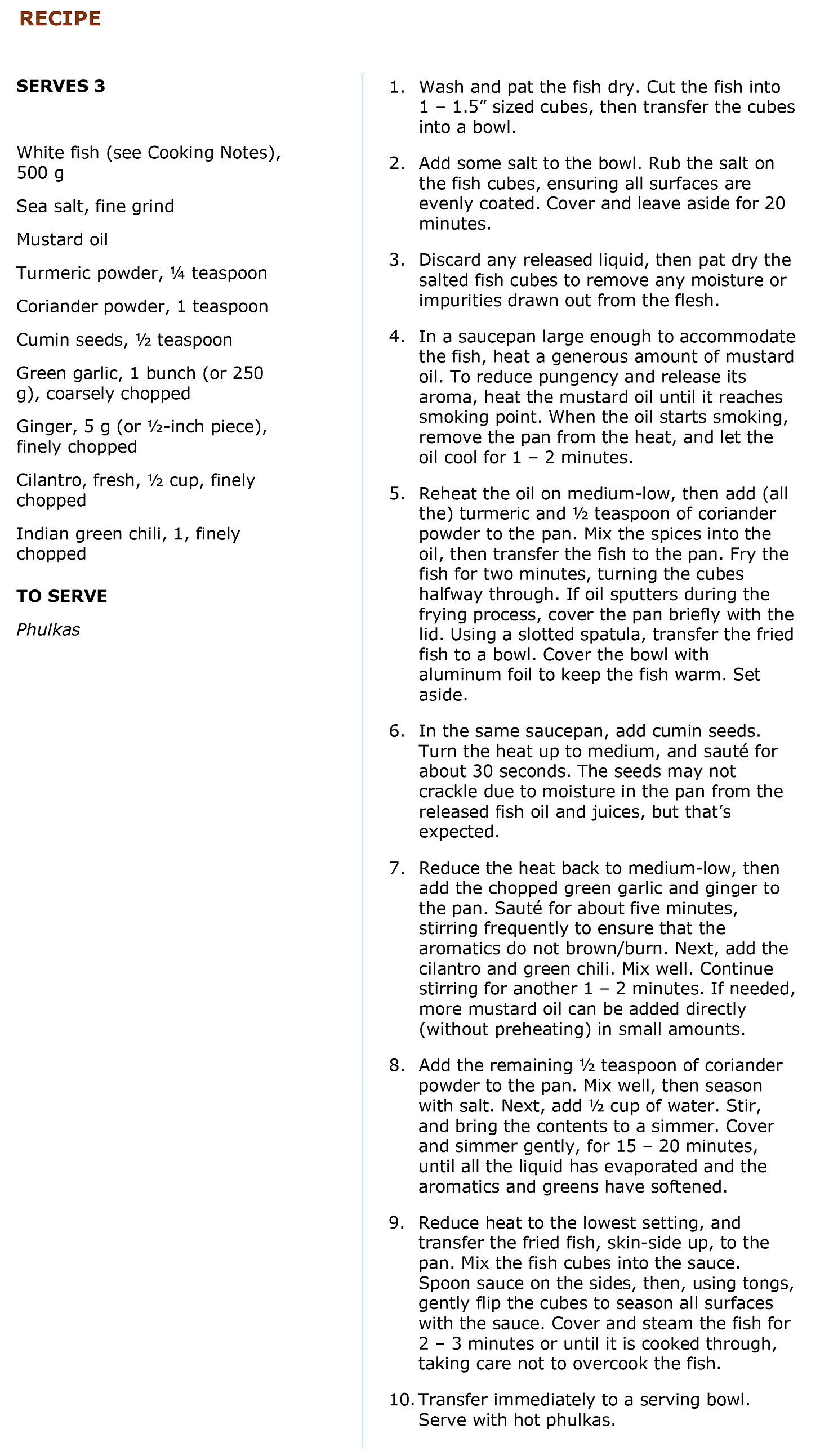

Green-Garlic Scented Fish

Mark the arrival of spring with this garlic-forward Sindhi preparation—once a staple, now fading from memory—where freshwater fish is gently steamed in an aromatic sauce infused with green garlic.

Story and recipe developed in collaboration with Neena Moorjani.

The Partition and the loss of a culinary identity

Pre-Partition Sindhi cuisine was deeply tied to its geography—rooted in the fertile plains of the Indus River and enriched by its access to the Arabian Sea. Fish curries and seafood dishes, fried, cooked in their own juices, or steamed in a garlic-rich sauce, were once a staple, blending the region’s maritime bounty—that included pomfret, carp, catfish, kingfish, hilsa, red snapper, grouper, threadfin and prawns—with the distinctive flavors of tamarind and local spices. However, when Hindu Sindhis were pushed out of Sindh by the Partition in 1947 and primarily resettled in landlocked regions of India, their cuisine underwent a significant shift. With fresh seafood and river fish no longer readily available, monetary constraints, and new cultural expectations, culinary trends were forced to adapt. Shaped by Hindutva signaling that discouraged the consumption of meat and fish, but whose adoption allowed assimilation with the local populaces that often eyed the Sufi-inspired Sindhi customs with suspicion, vegetarian dishes gradually took center stage. This piece will explore how migration shaped the Hindu Sindhi cuisine, forcing the displaced community to redefine its eclectic traditions within a more conservative culinary landscape.

The Partition was not just a political event; it was a massive rupture that severed communities from their ancestral lands, disrupted traditions, and erased entire culinary identities. While the geopolitical ramifications have been extensively documented, the cultural and culinary losses remain largely overlooked, perhaps because dominant narratives of Partition center around Punjab and Bengal, where land was violently exchanged between migrating Hindu and Muslim communities. This turbulent exchange, however, retained access to a familiar terrain, which allowed at least some level of continuity of customs and culinary traditions. In contrast, due to its majority Muslim population, the province of Sindh was never partitioned. It was handed over in its entirety to Pakistan, which triggered a mass exodus of Hindu Sindhis that left their foodways fractured from the land and ecosystems that had long sustained them.

Sindh—a region shaped by its riverine and coastal geography—is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the south, while the Indus River flows through its heart. Pre-Partition Sindhi diet included a generous amount of seafood, and dishes featuring prawns, pomfret, mullet, mackerel, kingfish, red snapper, grouper and threadfin were common. Additionally, river fish from the Indus, such as (the highly prized) hilsa, carp and catfish, were widely consumed. When Partition forced Hindu Sindhis to migrate, they were overwhelmingly settled—through government resettlement programs—in landlocked cities of India, such as Ahmedabad (Gujarat), Indore (Madhya Pradesh) and Ulhasnagar (Maharashtra). These locations were vastly different from Sindh’s littoral landscape, and direct access to fresh seafood and river fish became both scarce and expensive as Hindu Sindhis found themselves as refugees in a new geographical and socio-political reality.

Discover the full range of stories and recipes in the Culinary Index, and explore lesser-known ingredients in the Ingredient Spotlights—both now featured on Savor the Story homepage.

In addition to the loss of access to indigenous ingredients and monetary constraints, religious assimilation—critical to making “life viable”—played a significant role in shaping the post-Partition Sindhi diet in India. Yash Gupta examines this connection in “Meals and Migrations: Sindhi Culinary Memories of the Partition” (published in Media Technology and Cultures of Memory: Mapping Indian Narratives).

“Suspicion and rejection also engendered assimilation, specifically religious assimilation, as a means of making “life viable” (Hage 6). This was realised dually: first, by the saffronisation of Sindhi Hinduism, and, second, through devotion to holy saints. As aforementioned, Sindhi Hinduism is eclectic in conception, combining varying strands of Sikhism, Hinduism, and Sufism. Yet, since the “Islamic heritage of Sufism remains fairly clear” (Ramey 31), Sindhi Hinduism has marked a distinct departure from its Sufi roots. The shift is underwritten by strengthening Islamophobia and Hindutva ideologies emanating from the Matrabhoomi, India. (...) Dominance of saffron names has been augmented by the rising devotion to holy individuals such as Guru Radha Saomi and Swami Chinmayananda among Sindhis markedly after the Partition. Central to several of their teachings have been ideas of vegetarianism, tolerance, and self-improvement underpinned by Hindutvite messaging (Falzon 55).”

Not surprisingly, the matrabhoomi, or the motherland of Hindu Sindhis (India)—in contrast to the left-behind janmabhoomi, or its birthplace (Sindh, Pakistan)—molded the customs and traditions of the displaced community in its own shades. Take the example of the Sindhi script, which shifted from the widely used Perso-Arabic form to the now-dominant Devanagari version in India—due to the latter’s familiarity within the Indian linguistic landscape and its alignment with Hindi—as a result of the Partition. This shift was reinforced in 1967 when Sindhi was recognized as an official Indian language, and Devanagari gained widespread use in governmental and educational contexts (in India). This has created a script divide among Sindhis on the two sides of the border as Perso-Arabic remains the standard in Pakistan.

From a culinary standpoint, Partition-triggered migration shaped Hindu Sindhi foodways by producing a steady movement away from a non-vegetarian diet. Pre-Partition accounts suggest that a (significant) minority of Hindu Sindhis, approximately 30 – 40%, practiced vegetarianism. This group mainly included those from the higher-caste and urban communities. After Partition, two factors—in addition to availability and monetary constraints—contributed to an increase in vegetarianism. First, higher-caste Hindu Sindhis, particularly those from the mercantile and educated communities with traditionally higher rates of vegetarianism, migrated to India in larger numbers compared to those from lower-class and agrarian backgrounds. The latter demographic—being rooted in rural areas—was less affected by the violence and instability of the Partition, which was concentrated in urban districts of Sindh. This—compounded with the stronger ties of agrarian communities to the land—led to their migration in far lower numbers compared to those from towns and cities, such as Karachi, Sukkur and Hyderabad. Second, Hindu Sindhis predominantly settled in Indian states with historically high rates of vegetarianism, such as Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. These four states are home to large Sindhi communities, collectively accounting for over 90% of the total Sindhi population in the country.

Caste-driven migration patterns, accessibility and economic constraints, and geographical settlement trends profoundly shifted the dietary practices of Hindu Sindhis after the Partition. Recent estimates project vegetarianism among Hindu Sindhis (in India) to be significantly higher than the national average of 44% among Hindus in India (a number drawn from the 2021 Pew Research Center study), with some estimates placing it as high as 50 – 60%. While precise numbers are unavailable, qualitative evidence and oral narratives point to a notable, but gradual, increase in vegetarianism as the displaced community redefined its eclectic cuisine within the more conservative culinary landscape of India. Aligning with the new cultural and social expectations—and moving away from the Sufi-inspired traditions of Sindh—was key to both assimilation and survival. The already high rate of vegetarianism among the migrating demographic further reinforced this trend within the community, producing a generational shift.

As fish curries faded from the collective memory, Sindhi curry (or Sindhi kadhi)—a roasted chickpea-flour-based vegetarian stew that once coexisted with a large repertoire of fish and shellfish dishes—rose to prominence and, ultimately, emerged as the symbol of the lost homeland, becoming the defining Sindhi meal in India. The post-Partition transformation of Sindhi curry reflects how displaced communities preserve traditions while adapting to new environments. Yet, in this process, several time-honored and once-beloved fish preparations have begun to fade. I would like to close this post by highlighting one such dish: thoomwari macchi. Even though I grew up in a household where Sindhi food was cooked almost daily, I have only recently discovered this dish. It is not that the dish is never cooked in Sindhi households in India, but more that it has taken a back seat to others and risks being forgotten.

In Sindhi, “macchi” translates to “fish” and “thoom” to “garlic,” with thoomwari macchi being a garlic-centered seasonal fish preparation. The dish is seasonal because it relies on green garlic—the young garlic harvested before the bulb fully matures—that is available from late winter to early spring. Milder and more delicate than mature garlic, green garlic allows the dish to be garlic-forward without overwhelming the natural flavors of the fish. Its soft, scallion-like, texture offers a gentler bite compared to the sharpness and pungency of mature garlic. Like many older cultures that live in harmony with their environment, this dish also celebrates the bounty of the seasons, marking the end of winter’s bite and the arrival of spring.

When fish is fresh and well-prepared, no vegetable or meat can match the depth of its flavors. Celebrate the arrival of spring and keep the tradition alive with this beautiful and fragrant fish preparation—one to be remembered, cooked, and passed down.

COOKING NOTES

On Fish: Hilsa is the traditional fish of choice for this dish, but it is a very hard find outside South Asia. Hilsa can be replaced with other river fish, such as American shad or walleye. Shad will work particularly well because its flavor and texture closely resemble that of hilsa. And while freshwater fish are closest to the traditional choices, halibut offers a clean, flaky alternative when those aren’t available.

On Mustard Oil: Mustard oil—the traditional oil of choice—has a distinct, slightly pungent, taste and aroma that pair beautifully with the bold garlic-heavy profile of this dish. Mustard oil, however, can be hard to find outside South Asia due to controversies surrounding the presence of high levels of erucic acid in the oil. For more information, read Nik Sharma’s Serious Eats article, “The Truth About Mustard Oil: Behind the “For External Use Only” Label.” You can use mustard seed oil from Yandilla—a low erucic-acid variety—which is FDA-approved and alleviates these concerns. It is expensive, but a little goes a long way. Otherwise, substitute with a neutral variety, such as avocado oil.

On Spices: Buy spices, such as turmeric, coriander and cumin, at a spice store over a regular grocery store. For high-quality Indian spices, I would recommend the Reluctant Trading Experiment. It’s a game changer!

On Green Garlic: Green garlic is the young garlic harvested before the bulb fully matures, and it is also known as spring garlic. It can be found at a local produce store or at the farmer’s market. Green garlic is available from late winter to early spring, depending on the local weather. Milder winters lead to earlier arrival of the vegetable, typically at the end of the season, while harsher winters delay the arrival to spring.

On Indian Green Chili: As the name suggests, it can be found at Indian grocery stores. It can also be conveniently substituted by Thai chili pepper, which is similar in size and intensity and more widely available.

On Phulkas: Phulkas are soft, round, unleavened flatbreads made from whole wheat flour. Look for them at Indian grocery stores. They are sold under the names of chapati, roti or phulka, which will all work well. Phulkas, though, are lighter and fluffier, and my preference when I can find them. The traditional bread of choice for this dish, however, is dodo, which is a dense flatbread made from jowar (or sorghum) and not an easy find. Phulkas serve as a reasonable substitute.