Sautéed Dill Greens

This is an unusual recipe in which the dill is not just for garnish, as is almost always used, but it is cooked much in a similar manner to spinach or other greens with the added Indian flavors.

Story and recipe developed in collaboration with Jatin Sonavane and Sandhya Sonavane.

Rediscover your dill through the Mangs of India: A story of foraging for survival

A version of this piece was recently featured on Scribehound Food.

I stood at Sosio’s Produce stall in the Pike Place Market (in Seattle), initiating an all-too-familiar conversation with a vendor I had not encountered there before.

Me: “I need a lot of dill. Do you have more inside?”

Vendor: “Yes, how much do you need?”

Me: “Nine bunches, please.”

Vendor: “(Raising their eyebrows) Nine bunches!”

The vendor (often) returned with nine bunches of dill.

Vendor: “Do you own a restaurant?”

Me: “No.”

Vendor: “What will you do with all this dill then?”

Me: “My husband cooks it like spinach. He sautés the dill with garlic and some basic Indian spices. It shrivels during the process, making just enough for a meal for three.”

The replies that followed could span the gamut:

“Sounds delicious! If you could save some, I would love to try it.”

“Oh, how interesting.”

“(Shaking their head) That would be way too strong for me!”

These replies were hardly surprising. This is after all an unusual way to prepare and eat dill. In this recipe, dill is not just for garnish, as is almost always used, but it takes center stage. The dish, which we often cook at home, is Indian in origin and comes from my husband's family. It is so regional, however, that before he cooked this dish for me, I had never eaten dill in that way even though I also grew up in Bombay (India).

Having enjoyed many a plate of sautéed dill, which we usually eat with phulkas or rotis, I, finally, decided to investigate the origins of this recipe. Since dill is so ubiquitous, I expected to find examples of dill cooked in a similar manner in other cuisines. The uniqueness of this recipe became even more obvious when I could not find any evidence of it used more than just a garnish. What I found about the origins of the dish, however, was both fascinating and humbling at the same time.

The humble origins of this dish can be traced to the villages of western India—in Maharashtra—where dill was commonly foraged for survival by a historically marginalized people: the Mangs. The Mangs were one of the many people that constituted the class of “untouchables,” or Dalits, a toxic product of the hierarchical Hindu caste system. The practice of untouchability in Indian society, and the ensuing discrimination and dehumanization, can be traced back to as early as 400 AD and was, finally, outlawed through constitutional reforms in 1950. Foraging, now a term mostly restricted to higher-end food circles, was a means of survival for the Mangs.

This is another example of la cucina povera—literally, “the kitchen of the poor” in Italian—but from the other side of the globe. Born out of necessity, this cooking philosophy focuses on minimizing waste and transforming humble ingredients into hearty meals that are more than the sum of their parts. Maximizing the calorie content while keeping costs low was a required culinary tenet in the Dalit kitchen. Wild leafy vegetables, fiber-rich grains, and pulses were staples. Meat was rare, but when it was on the menu, it was usually in the form of cheaper cuts and offal that were rejected by those who were higher up in the pecking order. Not surprisingly, intestines, feet, epiglottis and blood pudding (called lakuti) were all part of the Dalit cuisine, and animal fat was commonly used in the place of ghee and oil, which were expensive. The use of ground peanuts as a substitute for oil was also prevalent.

As some Dalit authors begin to document their food history—and as we mark 75 years since the end of the cruel practice of untouchability—I want to highlight this unique recipe for dill to tell the story of these people and their struggles. In this recipe, dill is cooked much in a similar manner to spinach or other greens with the added Indian flavors: sautéed in oil with a healthy dose of garlic, tempered with cumin seeds, lentils and chili pepper, then finished off with a couple of basic Indian spices. The result is a bold, yet simple, nutrient-rich and aromatic dish of greens with a unique flavor. The dish is typically eaten with a flatbread made from barley or millet, called bhakri. Since bhakri is not easily accessible outside India, we enjoy our dill with phulkas or heaped on focaccia.

COOKING NOTES

On Moong Dal: It can be found at Indian grocery stores.

On Spices: Buy spices, such as cumin, coriander and turmeric, at a spice store over a regular grocery store. For high-quality Indian spices, I would recommend the Reluctant Trading Experiment. It’s a game changer!

On Chile de Árbol: This is a medium-to-hot intensity pepper from Mexico. It can be found at Mexican grocery stores or at a store that specializes in spices.

On Dill: Large bunches of dill would be best obtained from a local produce store or at the farmer’s market. Regular grocery stores typically sell dill in smaller sizes.

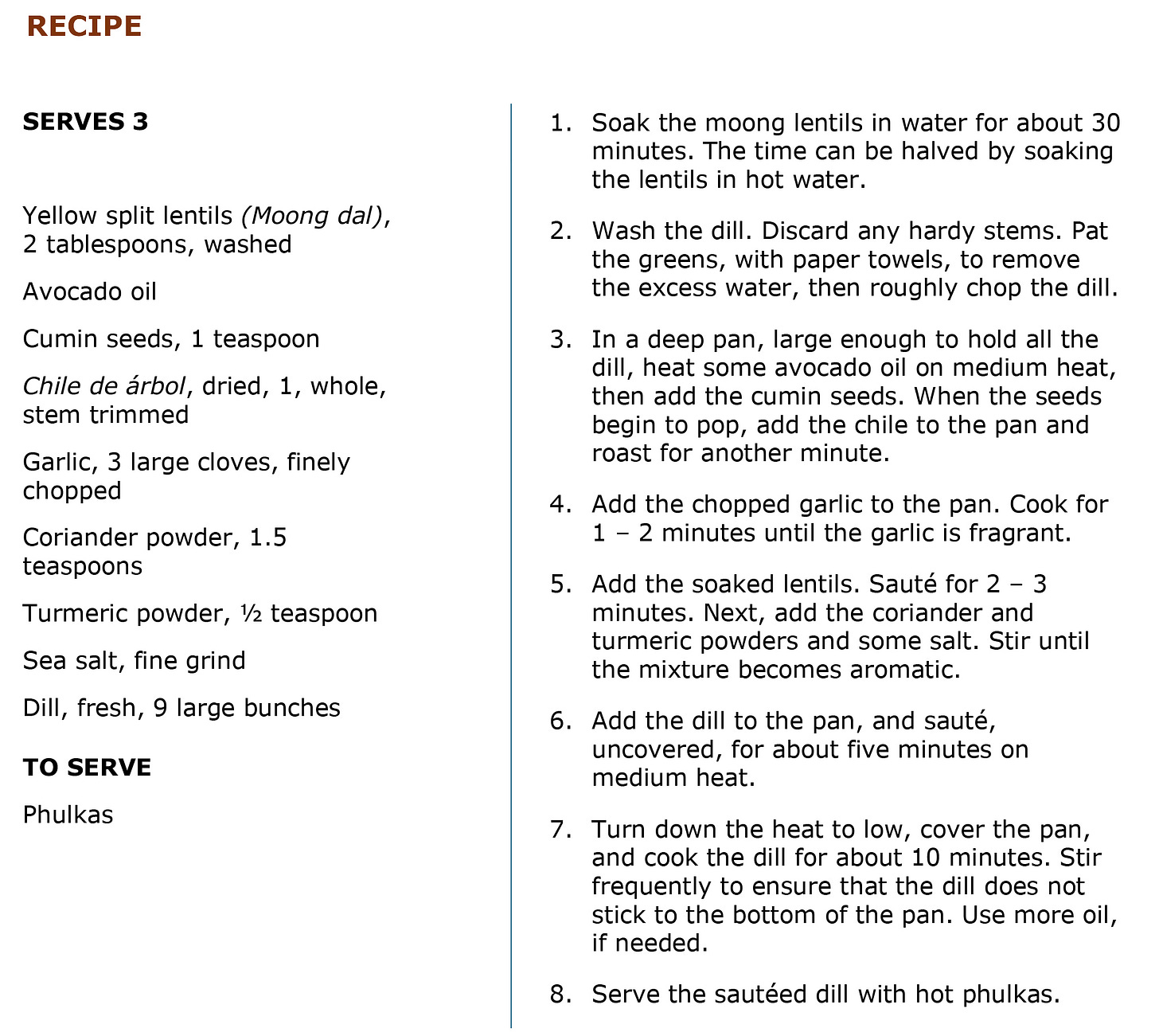

On Phulkas: Phulkas are soft, round, unleavened flatbreads made from whole wheat flour. Look for them at Indian grocery stores. They are sold under the names of chapati, roti or phulka, which will all work well with the sautéed dill. Phulkas, though, are fluffier and my preference when I can find them.