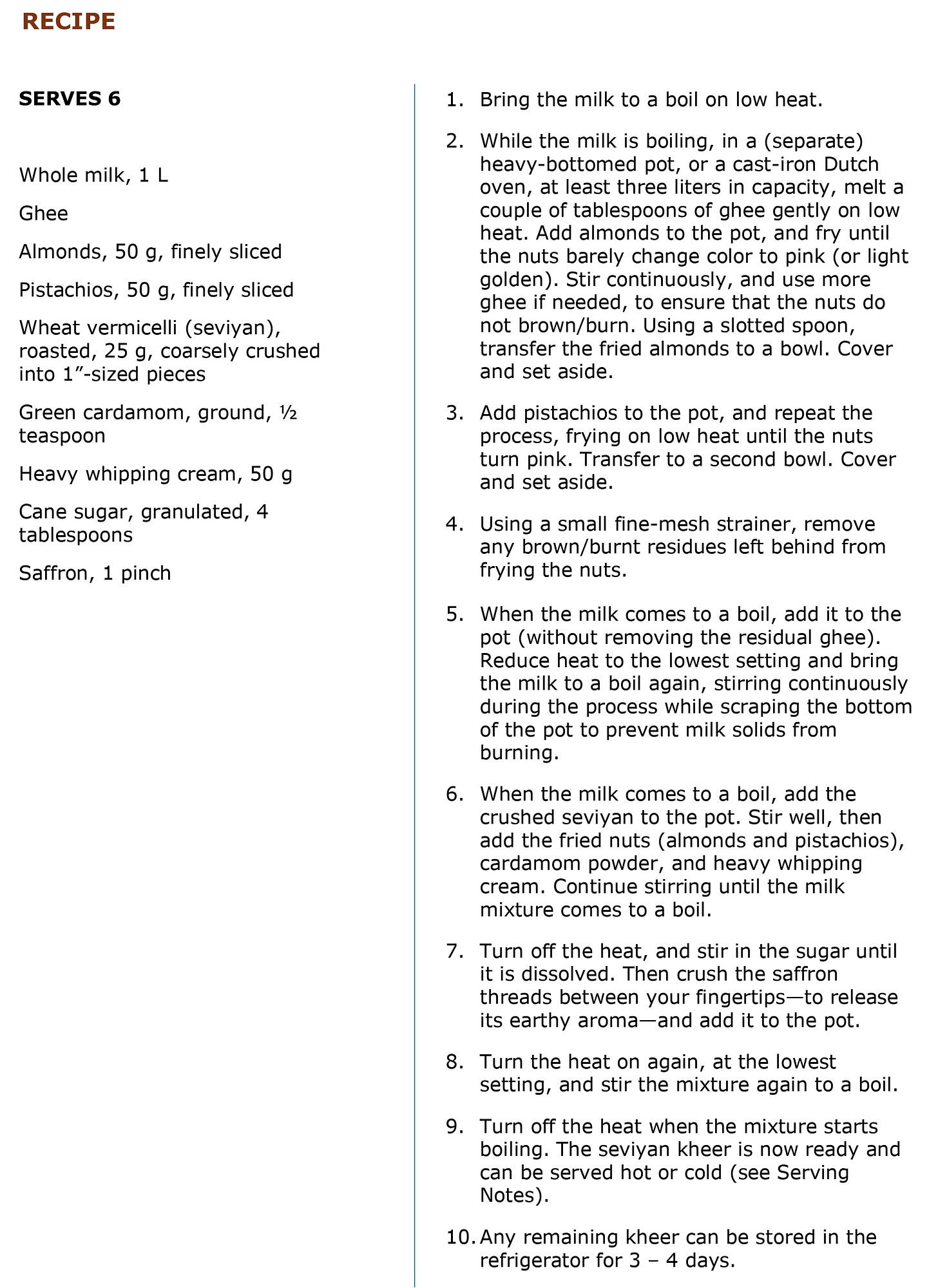

Creamy Vermicelli Milk Pudding

Deeply comforting to both cook and eat, this luxurious dessert—called seviyan kheer—traditionally prepared during Eid is made by gently simmering milk with sugar, wheat vermicelli, aromatics and nuts.

Story and recipe developed in collaboration with Shahnaz Patel and Neena Moorjani.

The flavor of Eid: A kheer to remember

If milk had been optional in my childhood, I’d have opted out every time. Plain milk was a no-go, and even getting me to drink hot chocolate was a struggle for my parents. Over time, I tried every trick I could think of to avoid milk, sometimes quietly emptying the whole cup down the basin or out the window. I still remember the expression of disbelief on my mom's face when she noticed I had finished my cup of milk within minutes. That surprise quickly turned to shock when she peered out the window. Unfortunately, the lesson I took from that day wasn't about honesty; rather, it was that I hadn't been smart enough. Aren't you glad you don't have to deal with such a child?

Since I didn't like the taste of milk, many desserts were also unappealing as the vast majority of sweets in India—where I grew up—are centered around milk. In fact, slowly cooking the milk with sugar until the volume is reduced to half, or even further, is the foundational technique behind most Indian desserts. The laborious simmering process—which involves almost-continuous stirring—thickens the milk, deepens its flavor, and gently caramelizes the sugar. Then, depending on the recipe, one or more aromatics, such as cardamom, rose water or saffron, are added to elevate it, finishing off with a garnish of nuts, rose petals, and sometimes silver or gold foil. Take the example of kheer, which is a kind of sweet milk pudding. In India, the two most common variants are made with rice or seviyan. “Seviyan,” rooted in Persian, is the word for “vermicelli.” The kind used in kheer is made from wheat, and the noodles are toasted before addition to the milk. Rice kheer tends to be creamier, though sometimes thick and starchy, while seviyan kheer is silkier in texture. These are luxurious desserts, and no two cooks will make the same kheer. Cooks labor over it for minutes to hours, and recipes are often closely guarded within families. As you may have guessed, kheer—whether made with rice or seviyan—wasn’t exactly a childhood favorite. It just felt like more milk to me! And it didn't help that my mom usually made a quick seviyan kheer, ready in about 20 minutes, that didn’t allow enough time for the flavors to transform.

Discover the full range of stories and recipes in the Culinary Index, and explore lesser-known ingredients in the Ingredient Spotlights—both now featured on Savor the Story homepage.

Seviyan kheer is traditionally prepared by Muslims at the end of Ramadan, on Eid al-Fitr, to mark the close of the fasting month. It is also enjoyed by many families during Eid al-Adha. Eid is a public holiday in India. Sumptuous bowls of kheer would arrive that day—always on Eid al-Fitr, and occasionally, with mutton, on Eid al-Adha—from our many Muslim neighbors in the building (and those bowls were never returned empty).

One late Eid (al-Fitr) afternoon, I came home tired and hungry after spending hours in the sun playing with my friends. I must have been about 10 years old. I went looking for my mom to fix me a snack, only to find that she was taking a nap, a rare luxury in her busy schedule as a working mother. Not wanting to wake her up, I rummaged through the kitchen cabinets in vain. Then I opened the fridge, only to discover at least 10 large bowls of seviyan kheer miraculously packed inside. I closed the door, hoping for better luck elsewhere. I repeated the exercise: bedroom to kitchen cabinets, then back to the fridge. This time, I paused longer. It was a sight to behold: seviyan kheer in beautiful bowls, each a slightly different shade of white, ivory or beige, garnished with almonds and/or pistachios. Some included charoli seeds or golden strands of saffron. The texture ranged from thin and silky to rich and creamy. No two were the same. As my stomach growled louder, resistance became futile. I picked the most decadent-looking bowl of kheer. It was creamy in texture, beige in color, flecked with generous slivers of almonds and pistachios, with a hint of golden from the saffron. Still a little hesitant, I took a spoonful. But the moment it touched my tongue, my reservations vanished. I was transported to a different place. Within minutes, the bowl was empty. It was pure pleasure, followed by a wave of remorse for all those years I had stubbornly refused the exquisite kheer our neighbors so generously sent on Eid. What a shame!

I set the empty bowl on the kitchen counter, still savoring the moment and eager to know which of our neighbors had made that incredible kheer. It turned out to be Shahnaz Aunty. My mom, without missing a beat, remarked that her kheer was always something special.

There was something magical about that bowl of kheer: the lush creaminess of the milk, the soft strands of vermicelli, the warmth of cardamom, and the floral lift of saffron that ended with the crunch of nuts. Every bite was layered, not just in flavor, aroma and texture, but in tradition and care, etching itself into my memory with every spoonful. It was a fine example of how a recipe—made from the same ingredients—transforms with each cook's instincts, patience and imagination, finding a new way to tell the same story and making it their own in the process. Like a soprano performing an opera whose story and musical score have remained unchanged for centuries, the cook gives the dish a new voice, transforming the experience of the audience, for better or worse. She might not have had a stage, but that bowl of kheer sang.

Kheer, in its many forms, has been cherished across centuries and borders. Its roots stretch deep, winding through Persia, Middle East, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent, a testament to how something as simple as milk, sugar and grain can carry the weight of tradition, celebration and nostalgia. Rice kheer originated in the Indian subcontinent over 2,000 years ago. It is one of the earliest known milk-based desserts in South Asia, with mentions in ancient Indian sources, such as Ayurvedic texts and the Puranas. Seviyan kheer (my personal favorite), on the other hand, is believed to have Perso-Arabic roots. The use of vermicelli in sweet milk puddings belongs to a broader tradition in Persia and the Middle East, where similar desserts like faloodeh (often described as Persian granita)—made with rice noodles—have been prepared since ancient times, dating back to the Achaemenid Empire (circa 550 – 330 BC). Seviyan kheer arrived in the Indian subcontinent through Islamic cultural and culinary influences of the Delhi Sultanate (dominant between 13th – 16th centuries) and was further refined during the Mughal era (between 16th – 18th centuries), whose power was centered in North India. Other variants of seviyan kheer include sheer khurma, which is a richer version that includes dates, more common in Afghanistan and Pakistan, but also some parts of North India, such as Lucknow (the capital city of the Nawabs of Awadh). In South India, the dish appears as semiya payasam, a festive dessert flavored with jaggery and coconut milk that is often served at weddings and during Onam celebrations.

During a recent conversation with my mom, I reminisced about Shahnaz Aunty's seviyan kheer, which is still the most memorable version of kheer I have had. Then, somewhat rhetorically, I wondered aloud, “Would she share her recipe?” knowing full well how closely such recipes are guarded in many families. My mom confidently replied, “Why not?” The thought of withholding recipes has never crossed my mom’s mind; she shares hers freely, no matter how unique, and expects the same from others. But I wasn't so sure. I still remember an Italian colleague's bewilderment—and near disbelief—when asked casually (by another colleague) if she'd share her mother's recipe. Oh, but how wrong I was! The next morning, Shahnaz Aunty's recipe appeared in my message window, forwarded by my mom. I stared at it in disbelief, which quickly turned into giddy excitement. Even my husband and son—who have never tasted her kheer—were thrilled by the possibility of experiencing that magic.

And magic it was! As I made the kheer—gently simmering milk with seviyan, fried nuts, sugar and aromatics—a familiar aroma returned, one I hadn’t encountered in over two decades. I knew I was on the right path and let the smell guide me through the unfamiliar terrain. I stirred the kheer patiently for over two hours until the milk turned creamy, the sugar began to caramelize, and the color deepened to a warm beige. With the scent of cardamom and saffron in the air and the quiet satisfaction of stirring something to life, it felt like a memory reborn—an old story retold, and a new one begun.

And the taste—otherworldly.

COOKING NOTES

On Ghee: Ghee is clarified butter from which water and milk solids have been removed, leaving behind pure fat that—unlike butter—can be stored at room temperature. It can be purchased in Indian or Pakistani grocery stores. In recent years, however, ghee can also be found at higher-end grocery stores, such as Whole Foods. Look for it on shelves that house oils.

On Nuts: I prefer to start with whole (unpeeled) nuts and slice them myself, though the process can be both laborious and time-consuming, especially in the quantities called for in this recipe. You can buy pre-sliced almonds and pistachios; the former is readily available, while the latter is typically sold at Indian or Pakistani grocery stores. Although high-quality whole nuts are easy to find, pre-sliced versions tend to be lower in quality, so give them a taste before adding them to the kheer. Whether to peel the nuts—or buy them peeled or unpeeled—is a matter of preference. I don’t peel mine, but I discard any loose skins that separate during slicing.

On Seviyan: Seviyan are wheat vermicelli noodles, sold in unroasted or roasted form. The unroasted variety is off-white or pale cream in color, while the roasted version ranges from light to medium brown. For this recipe, use pre-roasted (or browned) seviyan, which can be found in Indian or Pakistani grocery stores.

On Saffron: Saffron is primarily grown in Khorasan (Iran), Kashmir (India), Spain and Afghanistan, with its quality ranked in that order. While the Iranian, Kashmiri and Afghan varieties can be difficult to find in the U.S., Spanish saffron is more commonly available and remains a solid option.

SERVING NOTES

Seviyan kheer can be served hot or cold. To serve it hot, bring the kheer to a gentle boil over the lowest heat setting; this will also thicken the kheer and make it creamier. To serve it cold, refrigerate for at least two hours, preferably overnight. I like to serve the kheer warm on the day it’s prepared and chilled on the days that follow. Delayed gratification yields big dividends, with the flavors deepening each day. Or let the seasons decide—warm in winter, chilled in summer.